FANORONA VS RITHMOMACHY

FANORONA

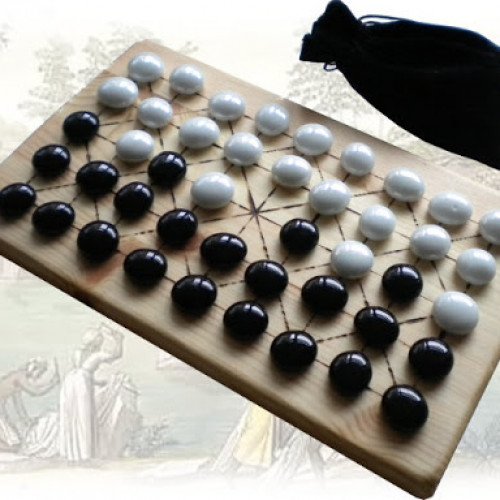

Fanorona (Malagasy pronunciation: [fə̥ˈnurnə̥]) is a strategy board game for two players. The game is indigenous to Madagascar. Fanorona has three standard versions: Fanoron-Telo, Fanoron-Dimy, and Fanoron-Tsivy. The difference between these variants is the size of board played on. Fanoron-Telo is played on a 3×3 board and the difficulty of this game can be compared to the game of tic-tac-toe. Fanoron-Dimy is played on a 5×5 board and Fanoron-Tsivy is played on a 9×5 board—Tsivy being the most popular. The Tsivy board consists of lines and intersections that create a grid with 5 rows and 9 columns subdivided diagonally to form part of the tetrakis square tiling of the plane. A line represents the path along which a stone can move during the game. There are weak and strong intersections. At a weak intersection it is only possible to move a stone horizontally and vertically, while on a strong intersection it is also possible to move a stone diagonally. A stone can only move from one intersection to an adjacent intersection. Black and white pieces, twenty-two each, are arranged on all points but the center. The objective of the game is to capture all the opponents pieces. The game is a draw if neither player succeeds in this. Fanorona is very popular in Madagascar. According to one version of a popular legend, an astrologer had advised King Ralambo to choose his successor by selecting a time when his sons were away from the capital to feign sickness and urge their return; his kingdom would be given to the first son who returned home to him. When the king's messenger reached Ralambo's elder son Prince Andriantompokondrindra, he was playing fanorona and trying to win a telo noho dimy (3 against 5) situation, one that is infamously difficult to resolve. As a result, his younger brother Prince Andrianjaka was the first to arrive and inherited the throne.

Statistics for this Xoptio

RITHMOMACHY

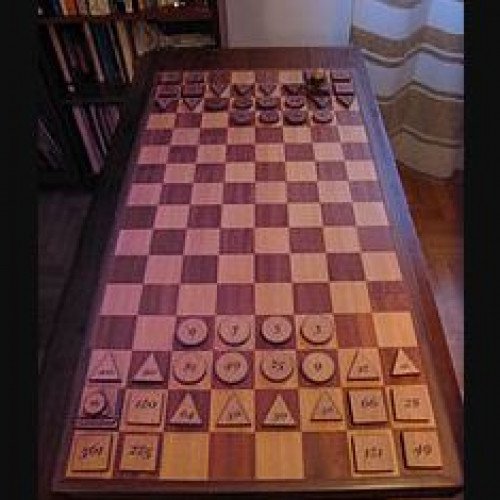

Rithmomachy (or Rithmomachia, also Arithmomachia, Rythmomachy, Rhythmomachy, or several other variants; sometimes known as The Philosophers' Game) is a highly complex, early European mathematical board game. The earliest known description of it dates from the eleventh century. A literal translation of the name is "The Battle of the Numbers". The game is much like chess, except most methods of capture depend on the numbers inscribed on each piece. It has been argued that between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, "rithmomachia served as a practical exemplar for teaching the contemplative values of Boethian mathematical philosophy, which emphasized the natural harmony and perfection of number and proportion. The game, Moyer argues, was used both as a mnemonic drill for the study of Boethian number theory and, more importantly, as a vehicle for moral education, by reminding players of the mathematical harmony of creation." Very little, if anything, is known about the origin of the game. Medieval writers attributed it to Pythagoras, but no trace of it has been discovered in Greek literature, and the earliest mention of it is from the time of Hermannus Contractus (1013–1054). The name, which appears in a variety of forms, points to a Greek origin, the more so because Greek was little known at the time when the game first appeared in literature. Based upon the Greek theory of numbers, and having a Greek name, it is still speculated by some that the game originated in Greek civilization, perhaps in the later schools of Byzantium or Alexandria. The first written evidence of Rithmomachia dates to around 1030, when a monk named Asilo created a game that illustrated the number theory of Boëthius' De institutione arithmetica, for the students of monastery schools. The rules of the game were improved shortly thereafter by another monk, Hermannus Contractus from Reichenau, and in the school of Liège. In the following centuries, Rithmomachia spread quickly through schools and monasteries in the southern parts of Germany and France. It was used mainly as a teaching aid, but gradually intellectuals started to play it for pleasure. In the 13th century Rithmomachia came to England, where famous mathematician Thomas Bradwardine wrote a text about it. Even Roger Bacon recommended Rithmomachia to his students, while Sir Thomas More let the inhabitants of the fictitious Utopia play it for recreation. The game was well enough known as to justify printed treatises in Latin, French, Italian, and German, in the sixteenth century, and to have public advertisements of the sale of the board and pieces under the shadow of the old Sorbonne.