DOWNFALL VS RITHMOMACHY

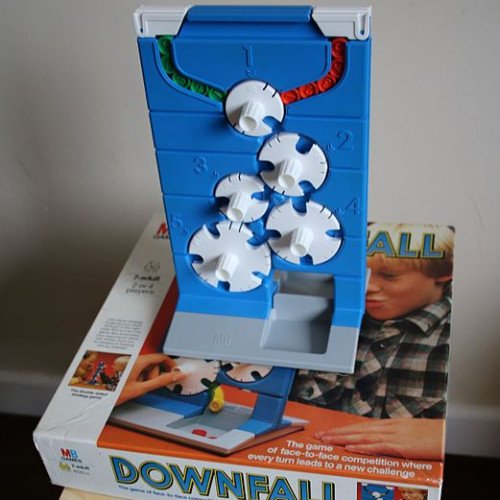

DOWNFALL

Downfall is a two-player game for players aged 7 and older, first marketed by the Milton Bradley Company in 1970. The game consists of a vertical board with five slotted dials on each side. Each player starts with ten numbered tokens or discs at the top of the board. The object of the game is to move the discs to the bottom of the board by turning the dials. Players alternate turns moving the dials and cannot move a dial that their opponent has just moved. The winner is the first player to move all of their discs into the tray at the bottom. An advanced version of the rules dictates that the discs arrive in the tray in numerical order. Since neither player can see the other's board, it is common to inadvertently advance - or hinder - the opponent's gameplay. The game rewards forward thinking and planning; players may try to "trap" their opponent into turning a dial that will advance their own disc, while trying to ensure that their own discs are not caught and dropped out of order. The game is currently available in the UK under the name New Downfall, manufactured and marketed by Hasbro. The new version follows the same rules but has a more futuristic design in red and yellow. The game's box art is parodied on the cover of Expert Knob Twiddlers, an album by Mike & Rich (Mike Paradinas & Richard D. James).

Statistics for this Xoptio

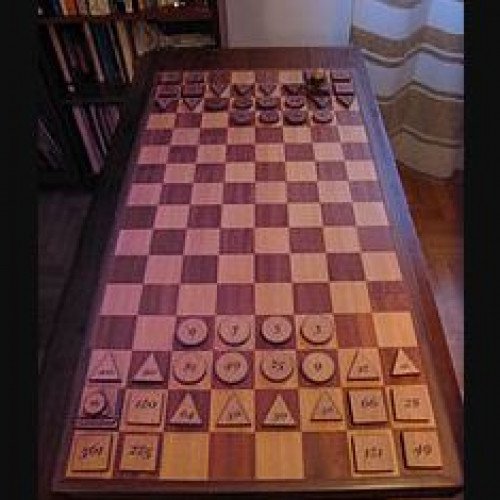

RITHMOMACHY

Rithmomachy (or Rithmomachia, also Arithmomachia, Rythmomachy, Rhythmomachy, or several other variants; sometimes known as The Philosophers' Game) is a highly complex, early European mathematical board game. The earliest known description of it dates from the eleventh century. A literal translation of the name is "The Battle of the Numbers". The game is much like chess, except most methods of capture depend on the numbers inscribed on each piece. It has been argued that between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, "rithmomachia served as a practical exemplar for teaching the contemplative values of Boethian mathematical philosophy, which emphasized the natural harmony and perfection of number and proportion. The game, Moyer argues, was used both as a mnemonic drill for the study of Boethian number theory and, more importantly, as a vehicle for moral education, by reminding players of the mathematical harmony of creation." Very little, if anything, is known about the origin of the game. Medieval writers attributed it to Pythagoras, but no trace of it has been discovered in Greek literature, and the earliest mention of it is from the time of Hermannus Contractus (1013–1054). The name, which appears in a variety of forms, points to a Greek origin, the more so because Greek was little known at the time when the game first appeared in literature. Based upon the Greek theory of numbers, and having a Greek name, it is still speculated by some that the game originated in Greek civilization, perhaps in the later schools of Byzantium or Alexandria. The first written evidence of Rithmomachia dates to around 1030, when a monk named Asilo created a game that illustrated the number theory of Boëthius' De institutione arithmetica, for the students of monastery schools. The rules of the game were improved shortly thereafter by another monk, Hermannus Contractus from Reichenau, and in the school of Liège. In the following centuries, Rithmomachia spread quickly through schools and monasteries in the southern parts of Germany and France. It was used mainly as a teaching aid, but gradually intellectuals started to play it for pleasure. In the 13th century Rithmomachia came to England, where famous mathematician Thomas Bradwardine wrote a text about it. Even Roger Bacon recommended Rithmomachia to his students, while Sir Thomas More let the inhabitants of the fictitious Utopia play it for recreation. The game was well enough known as to justify printed treatises in Latin, French, Italian, and German, in the sixteenth century, and to have public advertisements of the sale of the board and pieces under the shadow of the old Sorbonne.