BLOCKADE VS RITHMOMACHY

BLOCKADE

Blockade (also known as Cul-de-sac) is a strategy board game for two players with the motto "beat the barrier". It's played on a board with an 11x14 grid of spaces, barriers and 2 mobile playing pieces per player. The object of the game is to maneuver ones pieces around barriers and into the opponents starting spaces. The game is long out of production. Blockade was created by Philip Slater in 1975. In United States, it was published by Lakeside under the name Blockade. In France, Germany, Sweden, and United Kingdom the game was published by Lazy Days under the name Cul-de-sac (French, translation dead-end). The rules are simple, but it provides an interesting and deep game. Each player are given 2 pawns, 9 green walls (placed vertically), and 9 blue walls (placed horizontally). Pawns are placed on their starting locations on each of the four corners of the 11×14 board. First players' starting location is at [4,4] and [8,4], and the second players' is at [4,11] and [8,11]. The object of the game is for each player to get both their pawns to the starting locations of their opponent. The first to do so wins. On each turn, a player moves one pawn one or two spaces (horizontally, vertically, or any combination of the two) and places one wall anywhere on the board (useful for blocking off their opponent's move). Walls always cover two squares and must be placed according to their color (vertically or horizontally). Pawns may jump over other pawns that are blocking their path. Once players are out of walls, they keep moving pawns until one wins.

Statistics for this Xoptio

RITHMOMACHY

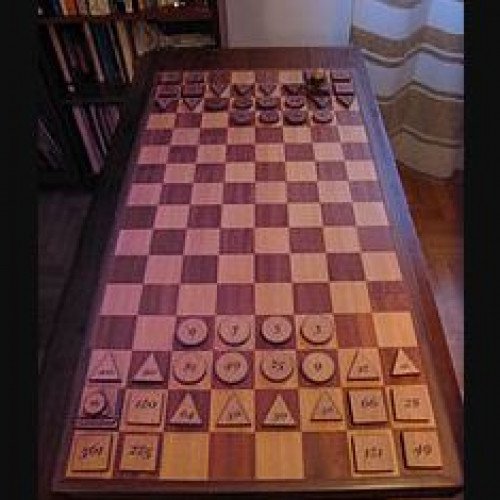

Rithmomachy (or Rithmomachia, also Arithmomachia, Rythmomachy, Rhythmomachy, or several other variants; sometimes known as The Philosophers' Game) is a highly complex, early European mathematical board game. The earliest known description of it dates from the eleventh century. A literal translation of the name is "The Battle of the Numbers". The game is much like chess, except most methods of capture depend on the numbers inscribed on each piece. It has been argued that between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, "rithmomachia served as a practical exemplar for teaching the contemplative values of Boethian mathematical philosophy, which emphasized the natural harmony and perfection of number and proportion. The game, Moyer argues, was used both as a mnemonic drill for the study of Boethian number theory and, more importantly, as a vehicle for moral education, by reminding players of the mathematical harmony of creation." Very little, if anything, is known about the origin of the game. Medieval writers attributed it to Pythagoras, but no trace of it has been discovered in Greek literature, and the earliest mention of it is from the time of Hermannus Contractus (1013–1054). The name, which appears in a variety of forms, points to a Greek origin, the more so because Greek was little known at the time when the game first appeared in literature. Based upon the Greek theory of numbers, and having a Greek name, it is still speculated by some that the game originated in Greek civilization, perhaps in the later schools of Byzantium or Alexandria. The first written evidence of Rithmomachia dates to around 1030, when a monk named Asilo created a game that illustrated the number theory of Boëthius' De institutione arithmetica, for the students of monastery schools. The rules of the game were improved shortly thereafter by another monk, Hermannus Contractus from Reichenau, and in the school of Liège. In the following centuries, Rithmomachia spread quickly through schools and monasteries in the southern parts of Germany and France. It was used mainly as a teaching aid, but gradually intellectuals started to play it for pleasure. In the 13th century Rithmomachia came to England, where famous mathematician Thomas Bradwardine wrote a text about it. Even Roger Bacon recommended Rithmomachia to his students, while Sir Thomas More let the inhabitants of the fictitious Utopia play it for recreation. The game was well enough known as to justify printed treatises in Latin, French, Italian, and German, in the sixteenth century, and to have public advertisements of the sale of the board and pieces under the shadow of the old Sorbonne.