"LEOPOLD BLOOM, ULYSSES, JAMES JOYCE" vs "RASKOLNIKOV, CRIME AND PUNISHMENT, FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY"

LEOPOLD BLOOM, ULYSSES, JAMES JOYCE

Leopold Bloom functions as a sort of Everyman—a bourgeois Odysseus for the twentieth century. At the same time, the novel’s depiction of his personality is one of the most detailed in all literature. Bloom is a thirty-eight-year-old advertising canvasser. His father was a Hungarian Jew, and Joyce exploits the irony of this fact—that Dublin’s latter-day Odysseus is really a Jew with Hungarian origins—to such an extent that readers often forget Bloom’s Irish mother and multiple baptisms. Bloom’s status as an outsider, combined with his own ability to envision an inclusive state, make him a figure who both suffers from and exposes the insularity of Ireland and Irishness in 1904. Yet the social exclusion of Bloom is not simply one-sided. Bloom is clear-sighted and mostly unsentimental when it comes to his male peers. He does not like to drink often or to gossip, and though he is always friendly, he is not sorry to be excluded from their circles. When Bloom first appears in Episode Four of Ulysses, his character is noteworthy for its differences from Stephen’s character, on which the first three episodes focus. Stephen’s cerebrality makes Bloom’s comfort with the physical world seem more remarkable. This ease accords with his practical mind and scientific curiosity. Whereas Stephen, in Episode Three, shuts himself off from the mat-erial world to ponder the workings of his own perception, Bloom appears in the beginning of Episode Four bending down to his cat, wondering how her senses work. Bloom’s comfort with the physical also manifests itself in his sexuality, a dimension mostly absent from Stephen’s character. We get ample evidence of Bloom’s sexuality—from his penchant for voyeurism and female underclothing to his masturbation and erotic correspondence—while Stephen seems inexperienced and celibate.

Statistics for this Xoptio

RASKOLNIKOV, CRIME AND PUNISHMENT, FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY

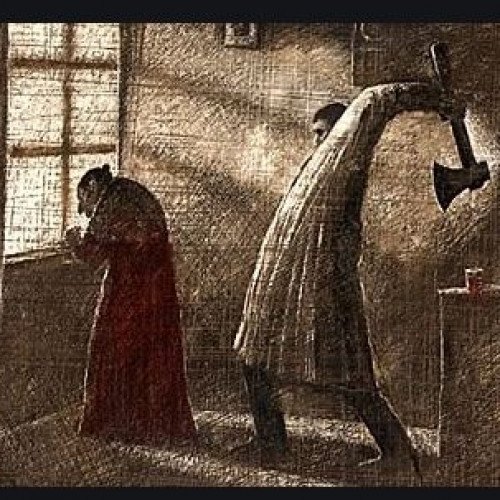

Raskolnikov is the protagonist of the novel, and the story is told almost exclusively from his point of view. His name derives from the Russian word raskolnik, meaning “schismatic” or “divided,” which is appropriate since his most fundamental character trait is his alienation from human society. His pride and intellectualism lead him to disdain the rest of humanity as fit merely to perpetuate the species. In contrast, he believes that he is part of an elite “superman” echelon and can consequently transgress accepted moral standards for higher purposes such as utilitarian good. However, that guilt that torments him after he murders Alyona Ivanovna and Lizaveta and his recurring faintness at the mention of the murders serve as proof to him that he is not made of the same stuff as a true “superman” such as Napoleon. Though he grapples with the decision to confess for most of the novel and though he seems gradually to accept the reality of his mediocrity, he remains convinced that the murder of the pawnbroker was justified. His ultimate realization that he loves Sonya is the only force strong enough to transcend his ingrained contempt of humanity. Raskolnikov’s relationships with the other characters in the novel do much to illuminate his personality and understanding of himself. Although he cares about Razumikhin, Pulcheria Alexandrovna, and Dunya, Raskolnikov is so caught up in his skeptical outlook that he is often unappreciative of their attempts to help him. He turns to Sonya as a fellow transgressor of social norms, but he fails to recognize that her sin is much different from his: while she truly sacrifices herself for the sake of others, he essentially commits his crime for his sake alone. Finally, his relationship with Svidrigailov is enigmatic. Though he despises the man for his depravity, he also seems to need something from him—perhaps validation of his own crime from a hardened malcontent.