Liberators of Latin America

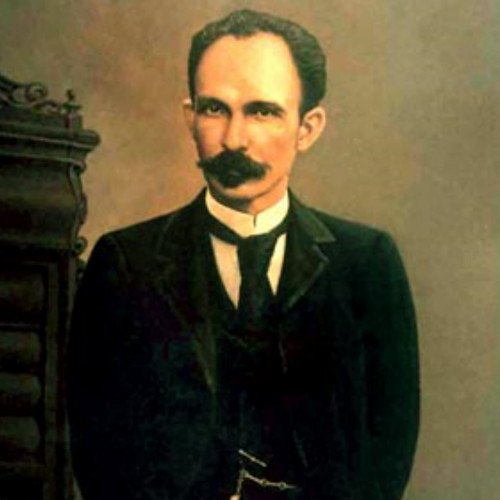

José Martí

José Julián Martí Pérez (Spanish pronunciation: [xoˈse maɾˈti]; January 28, 1853 – May 19, 1895) was a Cuban poet, philosopher, essayist, journalist, translator, professor, and publisher, who is considered a Cuban national hero because of his role in the liberation of his country. He was also an important figure in Latin American literature. He was very politically active and is considered an important revolutionary philosopher and political theorist.[1][2] Through his writings and political activity, he became a symbol of Cuba's bid for independence from the Spanish Empire in the 19th century, and is referred to as the "Apostle of Cuban Independence".[3] From adolescence, he dedicated his life to the promotion of liberty, political independence for Cuba, and intellectual independence for all Spanish Americans; his death was used as a cry for Cuban independence from Spain by both the Cuban revolutionaries and those Cubans previously reluctant to start a revolt. Born in Havana, Spanish Empire, Martí began his political activism at an early age. He traveled extensively in Spain, Latin America, and the United States, raising awareness and support for the cause of Cuban independence. His unification of the Cuban émigré community, particularly in Florida, was crucial to the success of the Cuban War of Independence against Spain. He was a key figure in the planning and execution of this war, as well as the designer of the Cuban Revolutionary Party and its ideology. He died in military action during the Battle of Dos Ríos on May 19, 1895. Martí is considered one of the great turn-of-the-century Latin American intellectuals. His written works include a series of poems, essays, letters, lectures, novel, and a children's magazine. He wrote for numerous Latin American and American newspapers; he also founded a number of newspapers. His newspaper Patria was an important instrument in his campaign for Cuban independence. After his death, one of his poems from the book, Versos Sencillos (Simple Verses) was adapted to the song "Guantanamera", which has become the definitive patriotic song of Cuba. The concepts of freedom, liberty, and democracy are prominent themes in all of his works, which were influential on the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío and the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral.[4] Following the 1959 Cuban Revolution, Martí's ideology became a major driving force in Cuban politics.[5] He is also regarded as Cuba's "martyr."

Statistics for this Xoptio

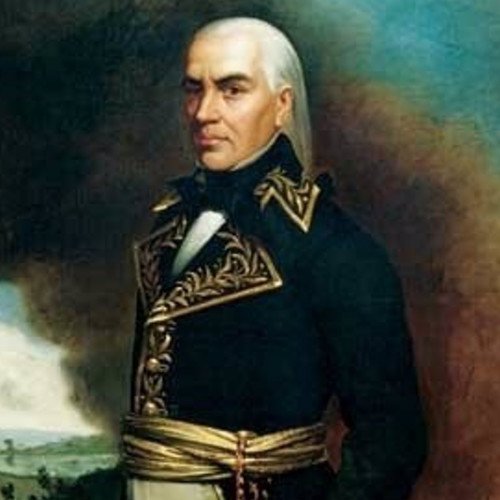

Francisco de Miranda

Sebastián Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinoza (March 28, 1750 – July 14, 1816), commonly known as Francisco de Miranda (American Spanish pronunciation: [fɾanˈsisko ðe miˈɾanda]), was a Venezuelan military leader and revolutionary. Although his own plans for the independence of the Spanish American colonies failed, he is regarded as a forerunner of Simón Bolívar, who during the Spanish American wars of independence successfully liberated much of South America. He was known as "The First Universal Venezuelan" and "The Great Universal American". Miranda led a romantic and adventurous life in the general political and intellectual climate that emerged from the Age of Enlightenment that influenced all of the Atlantic Revolutions. He participated in three major historical and political movements of his time: the American Revolutionary War, the French Revolution and the Spanish American wars of independence. He described his experiences over this time in his journal, which reached to 63 bound volumes. An idealist, he developed a visionary plan to liberate and unify all of Spanish America, but his own military initiatives on behalf of an independent Spanish America ended in 1812. He was handed over to his enemies and four years later, died in a Spanish prison. Miranda was born in Caracas, Venezuela Province, in the Spanish colonial Viceroyalty of New Granada, and baptized on April 5, 1750. His father, Sebastian de Miranda Ravelo, was a Spanish immigrant from the Canary Islands who had become a successful and wealthy merchant, and his mother, Francisca Antonia Rodríguez de Espinoza, was a wealthy Venezuelan.[1] Growing up, Miranda enjoyed a wealthy upbringing and attended the finest private schools. However, he was not necessarily a member of high society; his father faced some discrimination from rivals due to his Canarian roots. Miranda's father, Sebastian, always strove to improve the situation of the family, and in addition to accumulating wealth and attaining important positions, he ensured his children a college education. Miranda was first tutored by Jesuits, Jorge Lindo and Juan Santaella, before entering the Academy of Santa Rosa.[1] On January 10, 1762, Miranda began his studies at the Royal and Pontifical University of Caracas, where he studied Latin, the early grammar of Nebrija, and the Catechism of Ripalda for two years. Miranda completed this preliminary course in September 1764 and became an upperclassman. Between 1764 and 1766, Miranda continued his studies, studying the writings of Cicero and Virgil, grammar, history, religion, geography and arithmetic.[1] In June 1767, Miranda received his baccalaureate degree in the Humanities.[1] It is unknown if Miranda received the title of Doctor, as the only evidence in favor of this title is his personal testimony stating he received it in 1767, at age 17.